This is a waste of time. I hear this every time I sit down to read a book, every time I try to fumble out an essay, and sometimes this feels like the only voice I hear. At what point this voice began to form, I have no idea, but it emerged in my head and plagued me in doubt from the moment I told myself I wanted to be a reader and, for that matter, a writer.

I grew up as a fundamentalist Pentecostal, in a community that hardly recognized the value of reading. Of course, many fundamentalist Pentecostals read the Bible, a chapter a day, but beyond that, reading was hardly cherished as an activity worth pursuing. And the habit of reading philosophy, critical theory, and theology — this was viewed with suspicion. Philosophers, critical theorists, and theologians were viewed as wasteful elites, cloistered in the academy, and indifferent to the regular person. The culture contained an anti-intellectual populism. In the name of the public, the “common Man” (capitalized and gendered), many “down-to-earth” pentecostals denounced the habits of serious reading and writing as but the beginning of a descent into unchristian-elitist life.

This was more or less the orientation, and I can no longer escape it because it is within me, internalized as that vicious voice. So, for better or for worse, I wonder about reading. What can and does reading do? Why is it so threatening? And is it really a waste of time? I want to think reading has some relevance, some meaningful bearing on my life. Perhaps this is sentimental wishing.

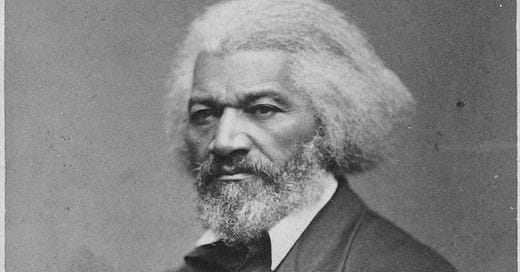

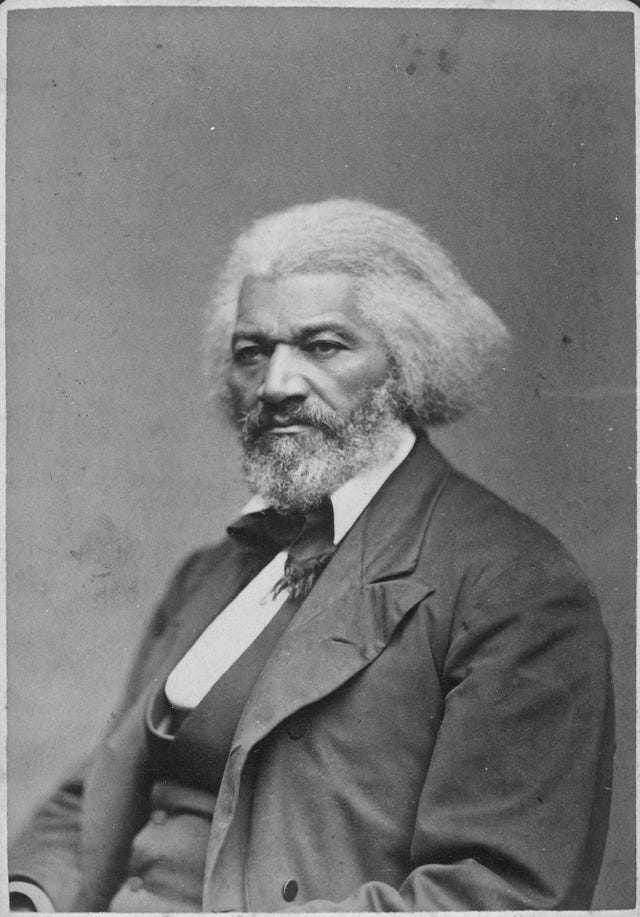

When the abolitionist Frederick Douglass first wrestled with these questions, he was enslaved. Douglass began learning how to read after he moved to Boston, but those lessons were cut short by his master, who believed that in learning how to read, Douglass would be introduced to ideas of freedom. A slave reading was not only illegal, Douglass recalls his master saying. “It was unsafe.”

Douglass eventually did learn to read, and he read everything he could — from collected oratories to abolitionist writings to the Bible. His master, it turns out, wasn’t wrong. Reading helped Douglass understand his “wretched condition,” and this is what made reading a “pathway from slavery to freedom.” It established a dialogue with others through which he could ask, parse out, and wonder about a world without slavery. More specifically, it helped him name his unfreedom and imagine his world as free. The danger of reading, it seems, lay in its capacity to conjure possible worlds through dialoging mediated by the written text.

This is what makes reading a humanizing act. To truly read is to be open both to the world of the text and to the world you bring to it, but on equal grounds — the insight of philosophers like Hans Georg Gadamer. Reading requires, against a hierarchical ordered society, that you take yourself as capable of both asking and responding to the text as an equal. Reading is an “I-Thou” act. With true reading, I must be willing to make a text a thou and, in turn, allow myself to be addressed as the thou of the author, even a dead author, even an author who wouldn’t wish to consider me a thou because of the color of my skin. An author, certainly a dead one, doesn’t have much of a choice at that point. Reading’s grace and judgement.

Now reading may be humanizing, but it is not a morally pure act. Fake news, for instance, generates power from our reading habits. The documentary “A Thousand Cuts” follows journalist Maria Ressa as she exposes how the Philippine government produced a whole network of fake news outlets to hide President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs. Duterte, in effect, remade a whole collective consciousness through dispersing and determining the news people read. Trump’s “Stop the Steal” is built around the same discourse of deception. If one can’t stop people from reading, then at least they can exploit it. Make it easy and cheap to find deceptive writing. Ban books. Censor journalists. Kill writers. Reading’s weaponization.

This is a 19th century phenomenon too, and Douglass is not unaware of this fact. It was the wife of Douglass’s master who first taught Douglass to read, and that was so he’d be more efficient at assigned tasks. Reading was the labor momentarily demanded by the slave system. And yet, Douglass still cherished reading, just as his master still felt the threat of a slave learning to read. Of reading, Douglass said: “I set out with high hopes, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read. … What he [his master] most dreaded, that I most desired. What he most loved, that I most hated.”

Through reading one can protest the limited vision of both the dead and the living. Commodities don’t read. But humans do. And Douglass did. In this, reading threatened the foundation of chattel slavery.

Updates:

What I’m reading: “Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative,” by Jane Allison. I’m also reading a collection of 52 Chekhov short stories translated and compiled by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Finally, I want to recommend the essay, “White Buffalo: Keep Your Mind in Hell, and Despair Not,” by Christian Wiman. It is an absolutely breathtaking and epic meditation on family, God, addiction, and grace.

What I’m listening to: Duval Timothy’s “Meeting with a Judas Tree.” I first discovered Duval Timothy through Kendrick Lamar, who sampled one of his songs on Mr. Morale. Haunting sounds with punchy melodies, “Meeting” is a great album if you’re wanting to listen to something that is both experimental and somber.